Seizing The Memes of Production

What is going on with NFTs and why are people willing to pay millions of dollars to own one? And what really happened with Gamestop back in January 2021?

Two letters in one month? A new record!

In today’s letter:

The NFT market is booming (again!). A “CryptoPunk” recently received a bid of almost $9.5 million. But why? Why would anyone pay such a crazy amount of money for a picture on the internet?

The SEC recently released a report on what actually happened with Gamestop and other meme stocks in early 2021. Turns out we were all wrong!

If you are not yet subscribed to the newsletter please consider subscribing (if you are getting this in your mailbox, don’t worry - you are already subscribed!).

Enjoy.

The NFT Manifesto

The NFT market is booming right now. In Q3 2021 the NFT market cap topped $14 billion with $10 billion in traded volume, a quarter-on-quarter increase of 700%. But why are so many people interested in buying JPEGs on the internet?

On October 1st, Twitter user @6529 released a Twitter thread on the future of NFTs which many have started referring to as “The NFT manifesto”. While I don’t agree with 100% of it, I think it’s a great intro to what NFTs actually are.

A Summary of the Thread

Society runs on Trusted Third Parties (TPPs) like Google, Citibank, and the IRS. These TPPs have an overwhelming influence on society and on citizen’s life. TPPs lead to micro problems such as anti-competitiveness and macro problems such as existential risks. The problem with society is that we tend to focus too much on small-scale problems while completely ignoring large-scale problems.

With Bitcoin, we solved decentralized consensus in a world where centralized consensus is the norm. Over time this evolved and led us to NFTs, non-fungible tokens. This branding is a disaster since very few actually know what ‘fungible’ means. Fungible means that items are mutually interchangeable. Non-fungible means the opposite of this, they are not mutually interchangeable. They are unique tokens.

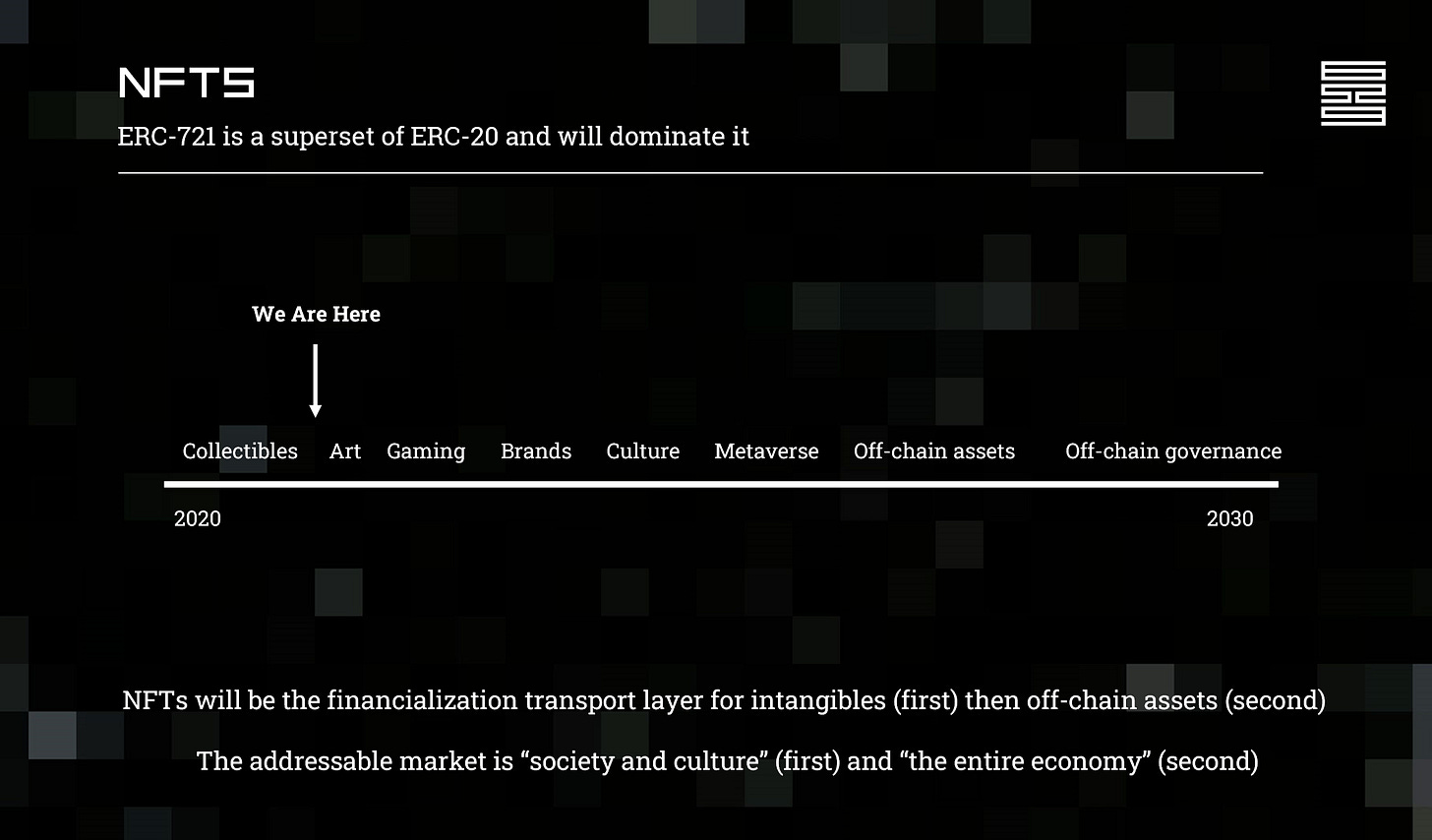

A lot of NFTs being released (“minted”) right now are going to zero. We’re in a crazy, speculative market AND we’re in uncharted territory. No one really knows what they are doing. But that doesn’t mean ALL NFTs are going to zero - or that NFTs are useless. NFTs isn't just art, it just happened to take off with art. It will continue to expand into brands, culture, and ultimately lead to decentralized alternatives to centralized organizations.

So, Where Are We Headed?

There’s an old story about a famous smuggler in Mexico. One day he is stopped at a police control trying to cross the border. The police check his truck and find nothing so they let him go. The following day he is stopped again. The police check his truck and again find nothing. This goes on for several weeks until the smuggler suddenly disappears. Years later one of the policemen sees the smuggler in a bar and begs the smuggler to tell him what was being smuggled.

“Trucks”, the smuggler replied.

Too many are focusing on what NFTs are currently being used for (art), that they can’t see the forest for the trees. While it might be hard to see the end-stage of NFTs, don’t forget Chris Dixon’s 2010 quote: “The next big thing will start out looking like a toy”. Remember that many thought the internet was just a fad because they couldn’t see the utility in it.

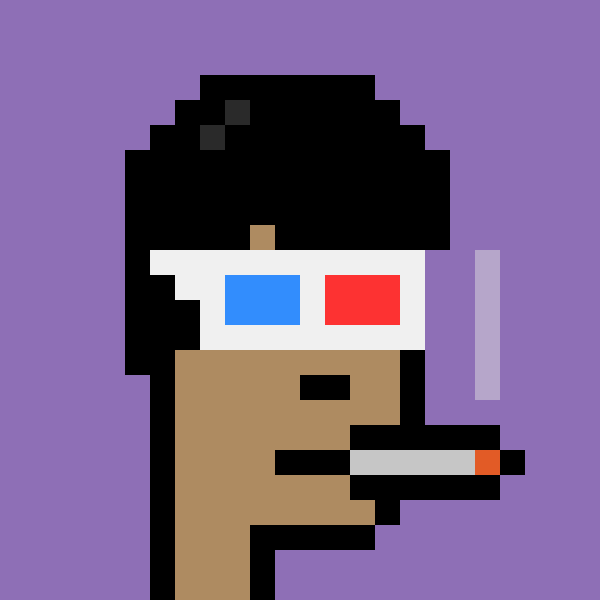

The other week CryptoPunk #6046 (pictured below) owned by @richerd received a bid of 2500 ETH, or roughly $9.5 million, from @poapxyz. @richerd politely declined the offer. This sounds crazy to most people, but to Richerd Punk #6046 represents more than just an image - it represents their brand.

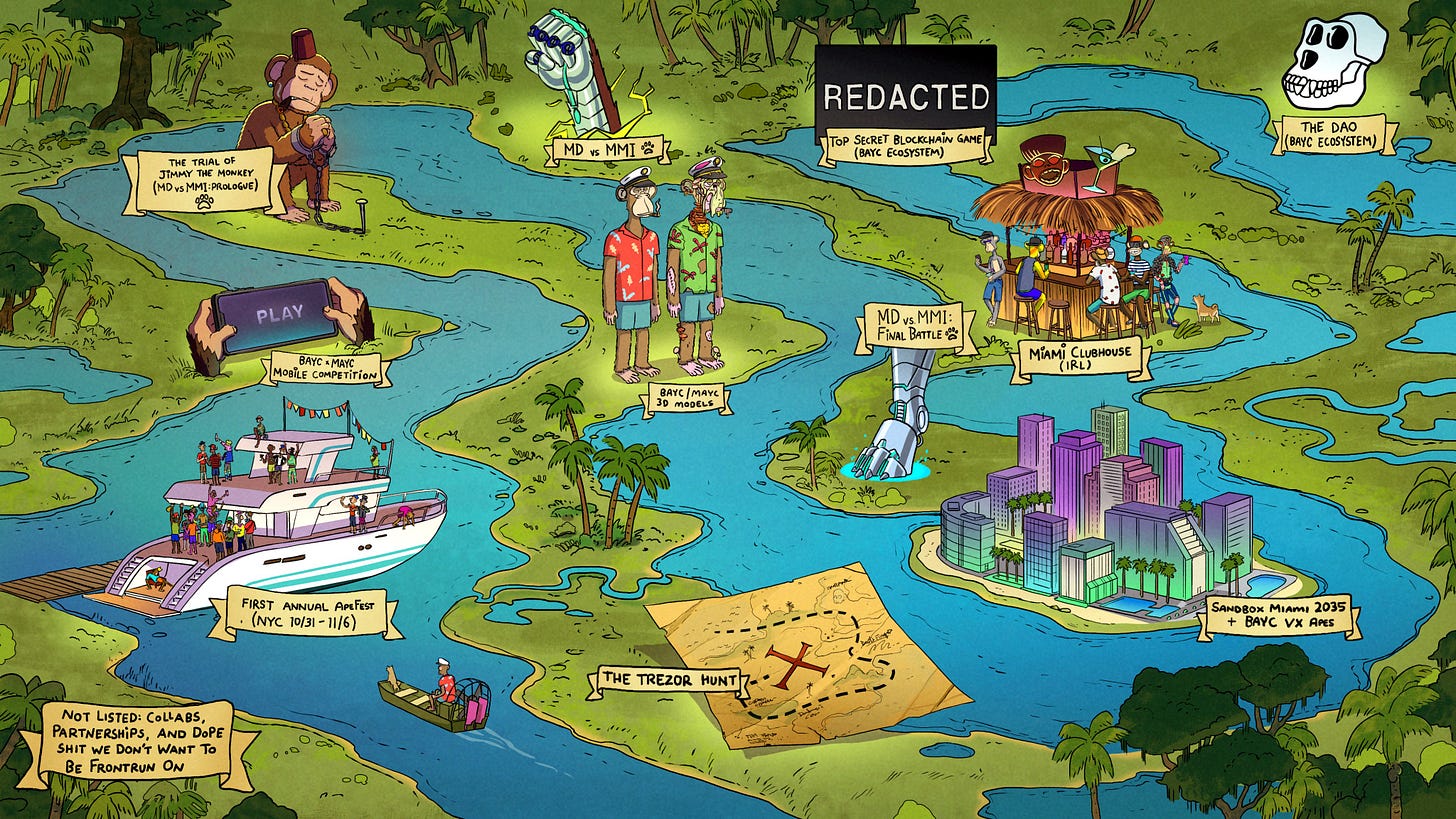

In the same week, Yuga Labs, the creators of Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT (BAYC), partnered with Guy Oseary. Oseary is a talent manager with clients like Madonna and U2 and is an early investor in companies like Airbnb, Robinhood, Spotify, and Opensea.

What’s the plan with this partnership? Most likely it’s to expand the relevancy of BAYC to a broader market and into pop culture. And they’re already well on their way. Popular NFT projects are quickly taking over profile pictures on popular social media platforms. Basketball legend Steph Curry is sporting a BAYC and rapper Snoop Dogg is donning a CryptoPunk.

The popularity of these NFT projects has driven the cost to buy one to extreme levels. Ten thousand unique BAYC NFTs were released in April 2021 for roughly ~$300. Six months later the lowest-priced BAYC goes for roughly $140 000. In September 2021, a set of 107 BAYC sold for $24.4 million at Sotheby’s. CryptoPunks, which were released for free in 2017, now go for at least half a million dollars a pop. But why?

Is BAYC just a silly collectible or is it a decentralized competitor to big brands and companies?

When cartoons like Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck first appeared they had no cultural relevance, but over time these cartoons became some of the most notable icons in human history. These individual cartoons laid the foundation for The Walt Disney Company, a $300 billion dollar corporation.

I’m not saying that Bored Apes are the next Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck, but Juga Labs is obviously trying to broaden the appeal and market for BAYC. And owning a Bored Ape means that you are an owner in the brand and in the culture.

To end this section, I’ll link to @NathanCRoth’s cheat sheet for NFTs. While I don’t think it’s a 1:1 comparison, I do think it’s rather clever.

The Big Short Squeeze

In January 2021, more than 100 stocks experienced large price moves or increased trading volume that significantly exceeded broader market movements - the most well-known being Gamestop (GME), but this also includes companies like AMC, Blackberry, and Nokia.

The recent 45 page SEC report titled “Staff Report on Equity and Options Market Structure Conditions in Early 2021” is an interesting read because the SEC has a birds-eye view of what actually transpired in January. They use data from the Consolidated Audit Trail where they track each individual order through its lifecycle - from customer to execution.

So, what did they find? Basically, everything that was reported on GME and other meme stocks (yes, they actually refer to them as meme stocks in the report) was incorrect. There was no considerable short squeeze, no gamma squeeze, no Citadel conspiracy. So what really happened?

A Long Time Coming

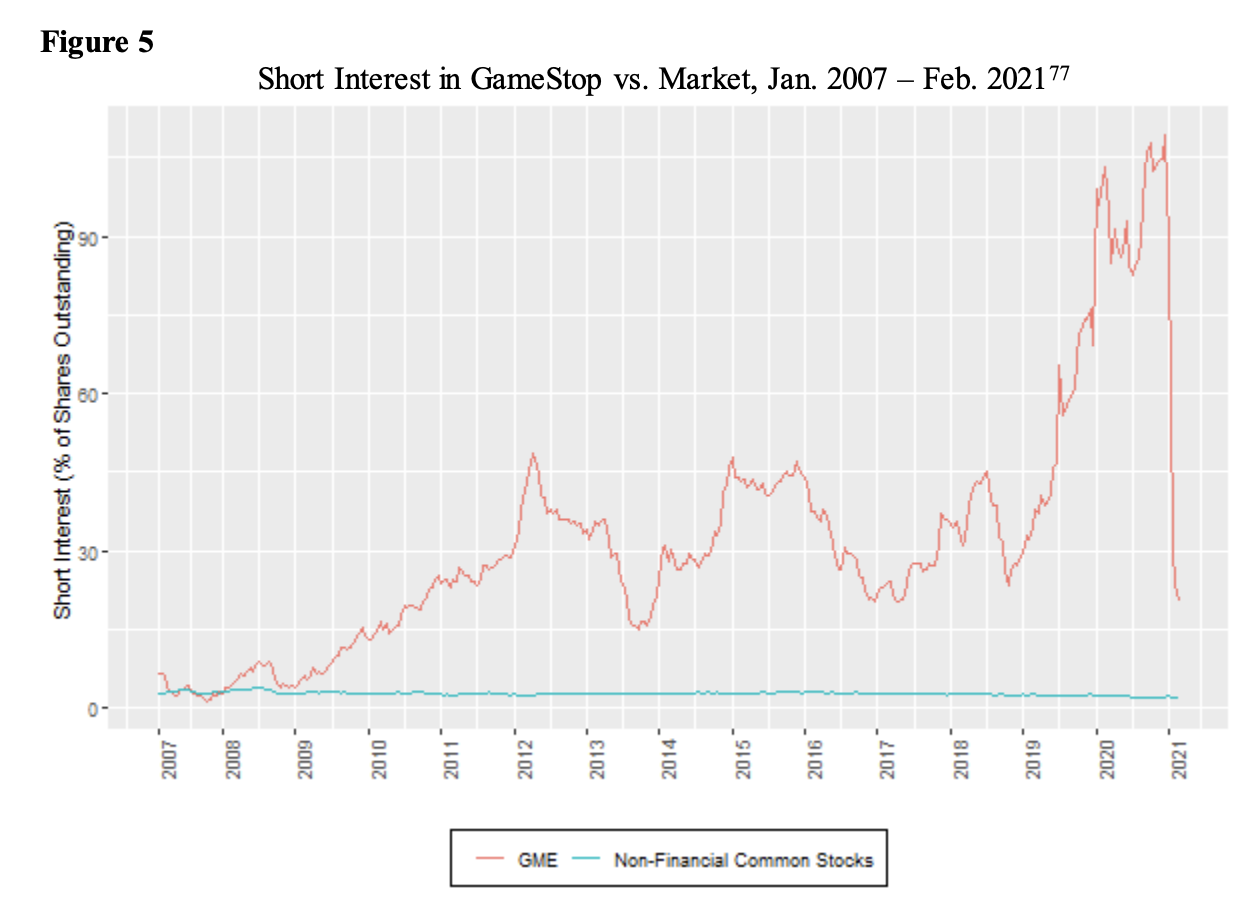

GME had been a highly shorted stock for quite a while. Even before the pandemic, the outlook for brick-and-mortar game retailers wasn’t too bright.

However, in 2020 GME’s stock started exhibiting higher volatility than in previous years, going from $6 at the start of the year to a little under $20 by the end of 2020.

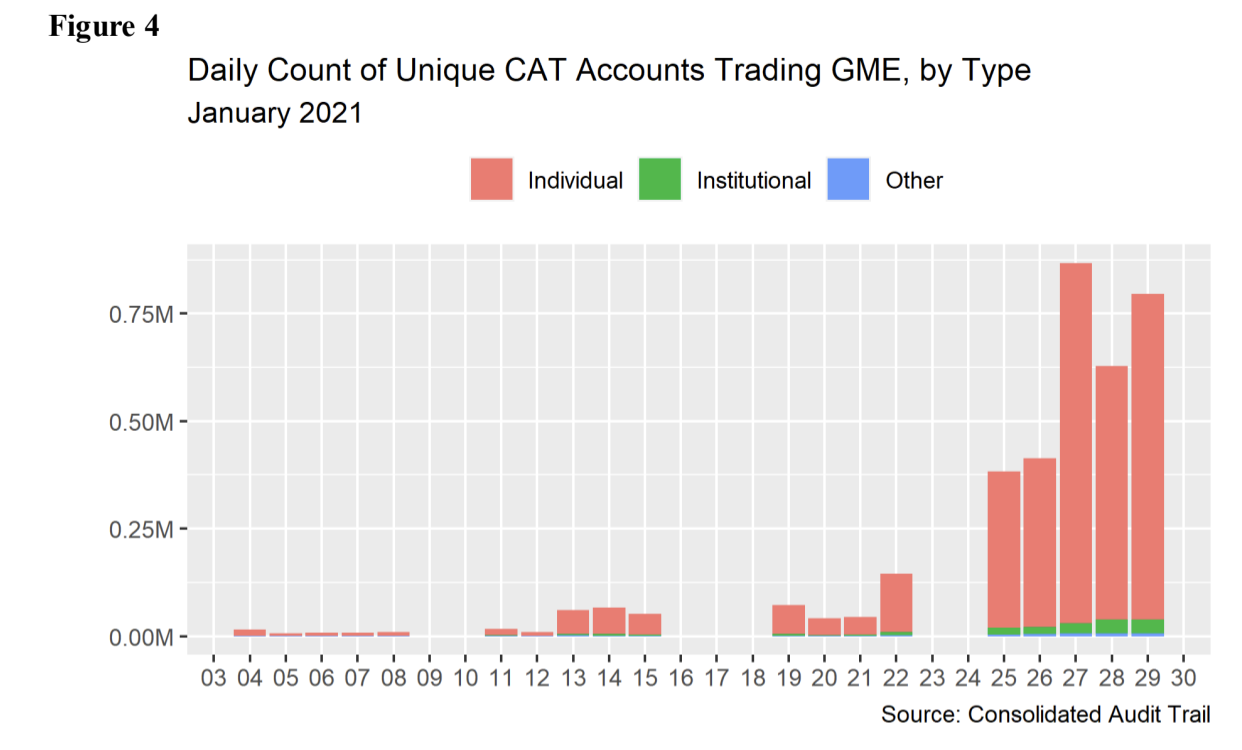

Price increases, trading interest, and social media interest all accelerated in 2021. From January 13 to 29, an average of 100 million GME shares traded per day, an increase of over 1,400 % from the 2020 average. And the rally culminated in GME reaching an intraday high of $483 on January 28.

The share price increase coincided with a sharp increase in the number of individual accounts actively trading GME which increased from less than 10,000 per day at the beginning of the year to nearly 900,000 per day by January 27.

What did these accounts look like? Unsurprisingly, they were mostly small accounts with young account owners. The median account balance in a Robinhood account is $240. During the pandemic, there was a surge in interest in retail trading and 6 million US accounts were opened in 2020, a 137% increase YoY, and 1 million of those accounts belonged to investors with an average age of 19.

The “Short Squeeze”

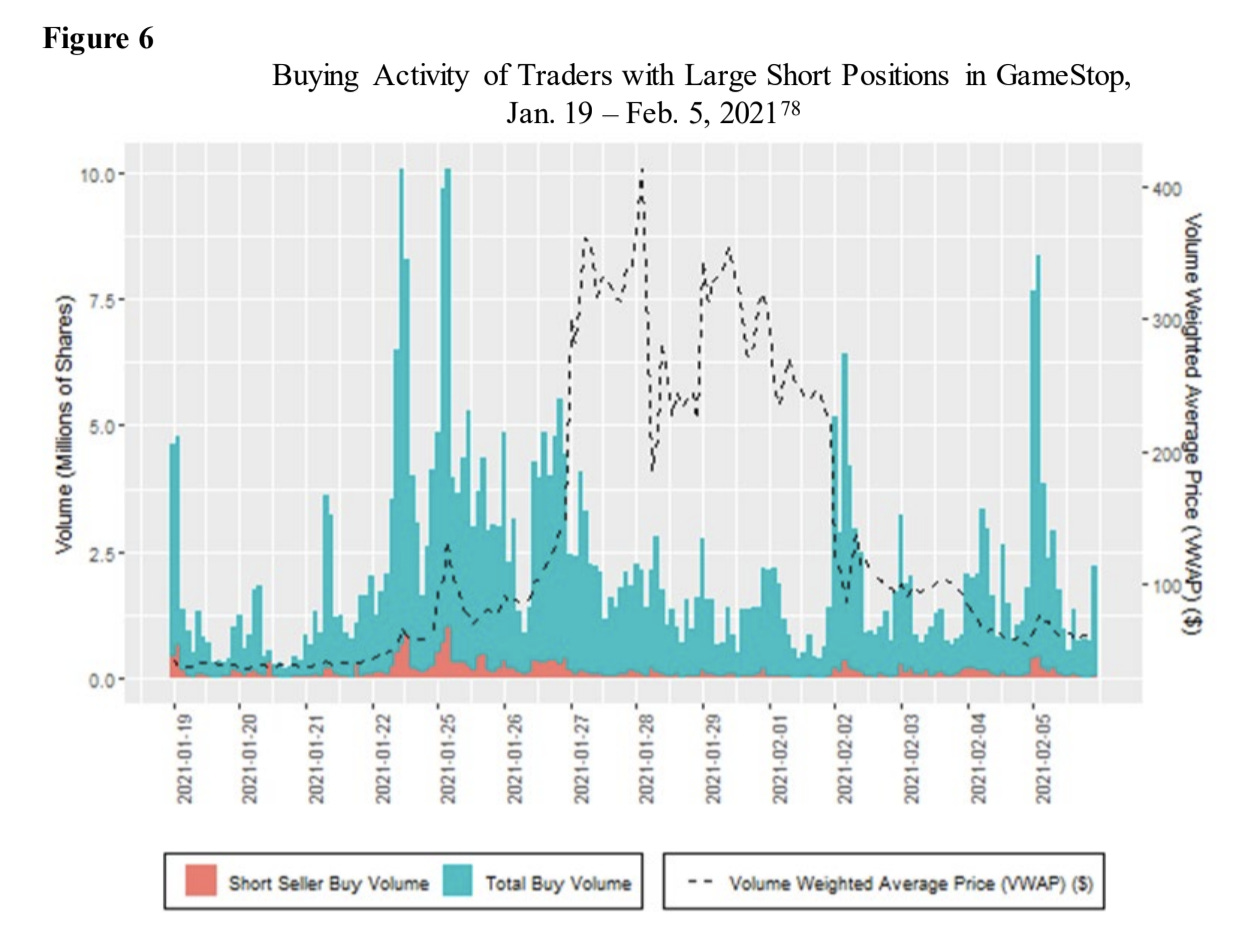

Back in January, an explanation given for the sharp increase in GME’s and other meme stock’s share price was that institutional investors were massively “short squeezed”. A short squeeze happens when an event, like a sudden increase in the price of the stock being shorted, triggers margin calls requiring short-sellers en masse to purchase shares to cover their short position. This puts upward pressure on the price which forces other short sellers to exit their position and so on. So did GME rally because of a short squeeze? Yes and no.

While some institutional accounts did have a significant short interest in GME (and other meme stocks) and needed to cover their short positions which contributed to GME’s price increase, this type of buying was only a small fraction of the overall buy volume. GME’s share price continued to rally after the direct effects of covering short positions had waned. While the underlying motivation of such buy volume “cannot be determined” according to the report it is likely that it was motivated by the desire to maintain a short squeeze. In the end, it was traders going long, not the buying-to-cover, that sustained the weeks-long rally in GME.

An interesting observation in the report is that while some institutions did realize significant losses due to their short positions, there were several institutions, mainly quantitative and high-frequency hedge funds, that bought the stock to be long. In the end, the SEC believes that hedge funds broadly were not significantly affected by investments in GME and other meme stocks.

In the report, it is argued that one of the main reasons the stock price disconnected so heavily from the fundamentals was that so few were actively willing to sell the stock short because it was unusually costly (and risky) to borrow shares. This leads to the implication that constraints on short selling may be a possible contributor to bubbles where stock prices rise above what may be justified by fundamentals.

Naked Shorts?

At the time, there were a lot of claims that hedge funds with huge short positions had not borrowed the stock which they are required to do (naked shorting). How else could GME have a short interest of over 100%?

Short selling involves the sale of a stock that the seller does not own. The seller then buys the stock back at a later date (and hopefully at a lower price) and gives it back to the lender. Short interest can exceed 100%—as it did with GME—when the same shares are lent multiple times by successive purchasers. If someone purchases a stock from a short seller and subsequently lends the stock out again, it will appear as if the stock was sold short twice for the purpose of the short interest calculation.

When a naked short sale occurs, the seller fails to deliver the securities to the buyer, and the SEC did observe spikes in fails to deliver in GME. However, GME did not experience perisitent fails to deliver at the individual clearing member level and most fails were able to be cleared relatively quickly. For the most part clearing members did not experience failures to deliver across multiple days. This means that there is no evidence of widespread naked short selling.

The Gamma Squeeze

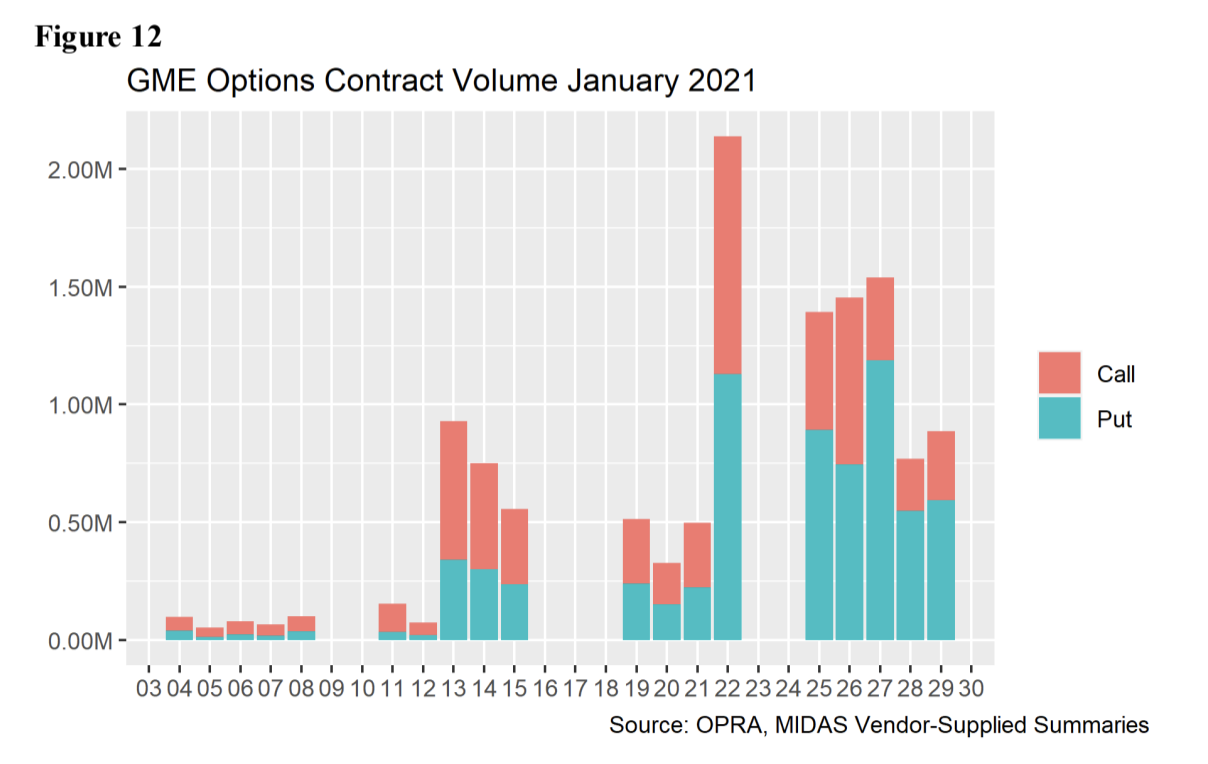

Another argument for GME’s sharp rise was a so-called “gamma squeeze” which occurs when market makers purchase stock to hedge the risk associated with writing call options on that stock which puts upward pressure on the stock price. The gamma squeeze argument was that retail investors bought a lot out of the money call options forcing market makers to hedge by buying the underlying stock.

While the SEC did find that GME options trading volume increased substantially, from only $58.5 million on January 21 to $2.4 billion on January 27, this increase in options trading volume was mostly driven by an increase in the buying of put, rather than call, options. By mid-January, 91% of non-market maker option volume came from retail investors and 66% of this came through Robinhood, Etrade, and TD Ameritrade. This is interesting because it shows that retail investors were either hedging their gains using options or betting that the price would fall. Further, data shows that market-makers were buying, rather than writing, call options.

Trading Halt Conspiracy

A common conspiracy was that brokers like Robinhood conspired with hedge funds and market makers to prevent further buying of GME and other meme stocks.

From the perspective of a retail investor, the lifecycle of a stock trade starts with an investor placing an order through their brokerage account. This order is then routed for execution in a trading center at a national securities exchange, an alternative trading system, or an off-exchange market maker. Once the order is executed, trade details are publicized and sent to the clearinghouse who affirms the trade by verifying the trade details. The process of settling a trade is done within two days of the trade date (often called “t+2”) by officially moving stock from the seller’s account and money from the buyer’s account.

A clearinghouse has risk management mechanisms that require brokers to keep cash (not customer money mind you) at the clearinghouse to guarantee trade settlement. In highly volatile trading environments where share prices whipsaw by hundreds of dollars, these brokers are required to post more margin (cash) to guard against an increased risk of defaults.

This risk management mechanism is what effectively led others in the transaction chain to pause and manage their risk exposure. The report details how much additional capital the brokerages were asked for.

On January 27, 2021, in response to market activity during the trading session, NSCC (Note: the clearing house) made intraday margin calls from 36 clearing members totaling $6.9 billion, bringing the total required margin across all members to $25.5 billion.

Of the $6.9 billion, $2.1 billion were intraday mark-to-market calls, while the remaining $4.8 billion was a special ECP charge.

Because these members’ ratios of excess risk versus capital were not driven by individual clearing member actions, but by extreme volatility in individual cleared equities, NSCC exercised its rules-based discretion to waive the ECP charge for all members on January 28, 2021.

Absent this waiver, one retail broker-dealer would have had an additional ECP charge of more than double its margin requirement of $1.4 billion on January 28, 2021

The clearinghouse actually decided to waive certain charges in an attempt to make life easier for both brokers and retail customers. It’s also important to note that the clearinghouse does not instruct brokers to stop trading individual stocks - it doesn’t have the ability to do that. This decision was made entirely by brokers in reaction to the margin calls and capital charges imposed by the clearinghouse.

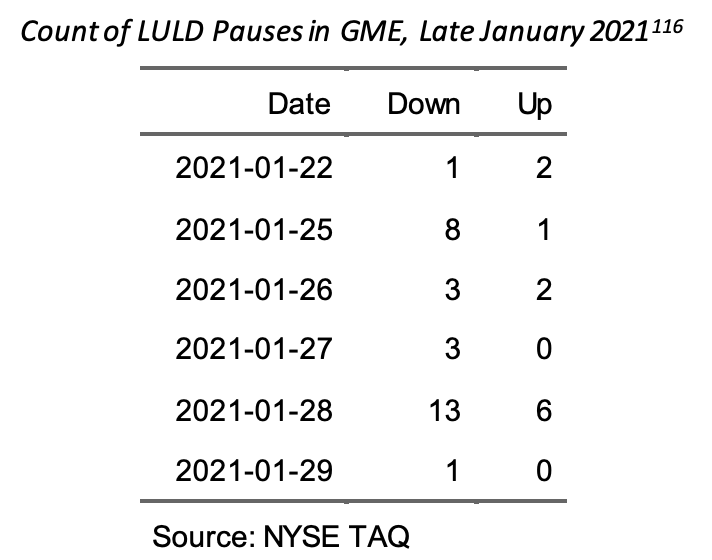

Trading halts were also issued because of the extreme volatility in the stocks.

As extreme intraday volatility in GME occurred, exchanges’ Limit-Up, Limit-Down (“LULD”) trading pauses were triggered on six trading days in late January. LULD is a trading mechanism that attempts to address extraordinary volatility in stocks. If either the National Best Bid equals the stock’s upper bound or the National Best Offer equals the stock’s lower bound for fifteen seconds, the stock’s trading will be paused for five minutes. Significant price movement in GME during January 2021 triggered 40 LULD pauses, compared with only one in all of 2020. On January 28 alone, 19 LULD pauses were triggered in GME.

Selling Order Flows

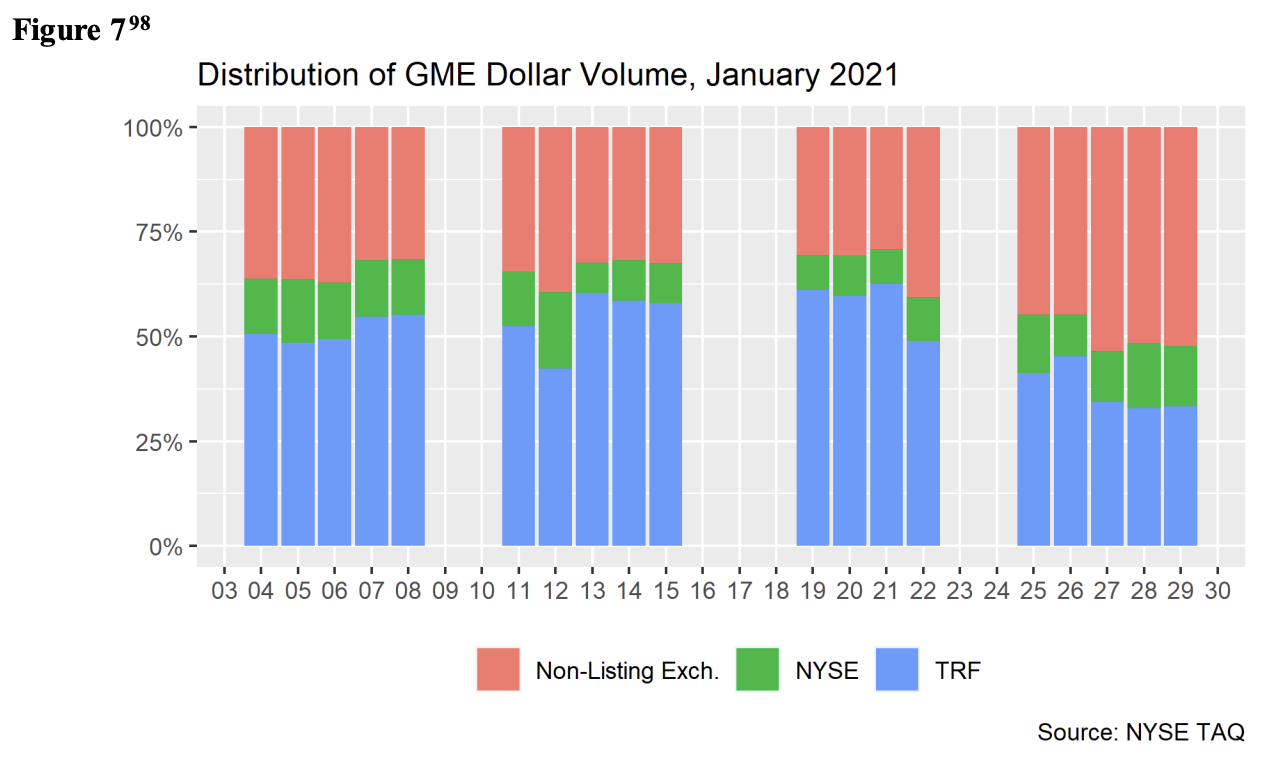

The events in January drew a lot of attention to the fact that brokers like Robinhood sell order flows to “off-exchange market makers” like Citadel. Many questioned why their orders were executed “off-exchange” due to concern that the stock was trading at different prices in different venues.

However, wholesalers like Citadel sought to avoid internalizing customer orders off-exchange as volatility increased to reduce potential losses when hedging became more difficult. On January 28th, over 67% of retail order flow was routed to exchanges to be executed.

In the end, it was a positive sentiment, not the buying-to-cover, gamma squeeze, or a Citadel Conspiracy that sustained the weeks-long price appreciation of the Gamestop stock.

End

That’s all from me folks. If you enjoyed this letter and still aren’t subscribed please click the button below. It’s free.